History Of Submarines on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the submarine spans the entire history of human endeavour as mankind has since early civilisation sought to explore and travel

The concept of underwater combat has roots deep in antiquity. There are images of men using hollow sticks to breathe underwater for hunting at the temples at Thebes, but the first known military use occurred during the siege of Syracuse (415–413 BC), where divers cleared obstructions, according to the ''History of the Peloponnesian War''. At the

The concept of underwater combat has roots deep in antiquity. There are images of men using hollow sticks to breathe underwater for hunting at the temples at Thebes, but the first known military use occurred during the siege of Syracuse (415–413 BC), where divers cleared obstructions, according to the ''History of the Peloponnesian War''. At the  Although there were various plans for submersibles or submarines during the

Although there were various plans for submersibles or submarines during the  Drebbel's submarine was propelled by oars. The precise nature of this submarine is unclear, it may be possible that it resembled a bell towed by a boat. Two improved types were tested in the

Drebbel's submarine was propelled by oars. The precise nature of this submarine is unclear, it may be possible that it resembled a bell towed by a boat. Two improved types were tested in the  Between 1690 and 1692, the French physicist

Between 1690 and 1692, the French physicist

The first American military submarine was in 1776, a hand-powered egg-shaped (or acorn-shaped) device designed by the American

The first American military submarine was in 1776, a hand-powered egg-shaped (or acorn-shaped) device designed by the American

In 1800, the

In 1800, the  In 1863 the was built by the

In 1863 the was built by the

The first submarine that did not rely on human power for propulsion was the

The first submarine that did not rely on human power for propulsion was the  The first air independent and

The first air independent and  The first such boat was the ''Nordenfelt I'', a 56 tonne, vessel similar to Garret's ill-fated ''

The first such boat was the ''Nordenfelt I'', a 56 tonne, vessel similar to Garret's ill-fated ''

In France, the early electric submarines ''Goubet I'' and ''Goubet II'' were built by the civil engineer, Claude Goubet. These boats were also unsuccessful, but they inspired the renowned naval architect Dupuy de Lôme to begin work on his submarine – an advanced electric-powered submarine almost 20 metres long. He didn't live to see his design constructed, but the craft was completed by Gustave Zédé in 1888 and named the . It was one of the first truly successful electrically powered submarines, and was equipped with an early periscope and an electric gyrocompass for navigation. It completed over 2,000 successful dives using a 204-cell battery. Although the ''Gymnote'' was scrapped for its limited range, its side hydroplanes became the standard for future submarine designs.

The

In France, the early electric submarines ''Goubet I'' and ''Goubet II'' were built by the civil engineer, Claude Goubet. These boats were also unsuccessful, but they inspired the renowned naval architect Dupuy de Lôme to begin work on his submarine – an advanced electric-powered submarine almost 20 metres long. He didn't live to see his design constructed, but the craft was completed by Gustave Zédé in 1888 and named the . It was one of the first truly successful electrically powered submarines, and was equipped with an early periscope and an electric gyrocompass for navigation. It completed over 2,000 successful dives using a 204-cell battery. Although the ''Gymnote'' was scrapped for its limited range, its side hydroplanes became the standard for future submarine designs.

The

The turn of the 20th century marked a pivotal time in the development of submarines, with a number of important technologies making their debut, as well as the widespread adoption and fielding of submarines by a number of nations.

The turn of the 20th century marked a pivotal time in the development of submarines, with a number of important technologies making their debut, as well as the widespread adoption and fielding of submarines by a number of nations.  Meanwhile, the French steam and electric '' Narval'' was commissioned in June 1900 and introduced the classic double-hull design, with a pressure hull inside the outer shell. These 200-ton ships had a range of over underwater. The French submarine ''Aigrette'' in 1904 further improved the concept by using a diesel rather than a gasoline engine for surface power. Large numbers of these submarines were built, with seventy-six completed before 1914.

By 1914, all the main powers had submarine fleets, though the development of a strategy for their use lay in the future.

At the start of

Meanwhile, the French steam and electric '' Narval'' was commissioned in June 1900 and introduced the classic double-hull design, with a pressure hull inside the outer shell. These 200-ton ships had a range of over underwater. The French submarine ''Aigrette'' in 1904 further improved the concept by using a diesel rather than a gasoline engine for surface power. Large numbers of these submarines were built, with seventy-six completed before 1914.

By 1914, all the main powers had submarine fleets, though the development of a strategy for their use lay in the future.

At the start of  The British also experimented with other power sources. Oil-fired steam turbines powered the British "K" class submarines built during the

The British also experimented with other power sources. Oil-fired steam turbines powered the British "K" class submarines built during the

Various new submarine designs were developed during the interwar years. Among the most notable were

Various new submarine designs were developed during the interwar years. Among the most notable were

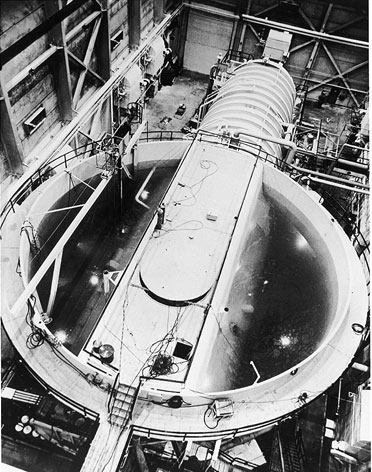

In the 1950s,

In the 1950s,

The first submarines had only a porthole to provide a view to aid navigation. An early periscope was patented by

The first submarines had only a porthole to provide a view to aid navigation. An early periscope was patented by

During the

During the

The first time military submarines had significant impact on a war was in

The first time military submarines had significant impact on a war was in

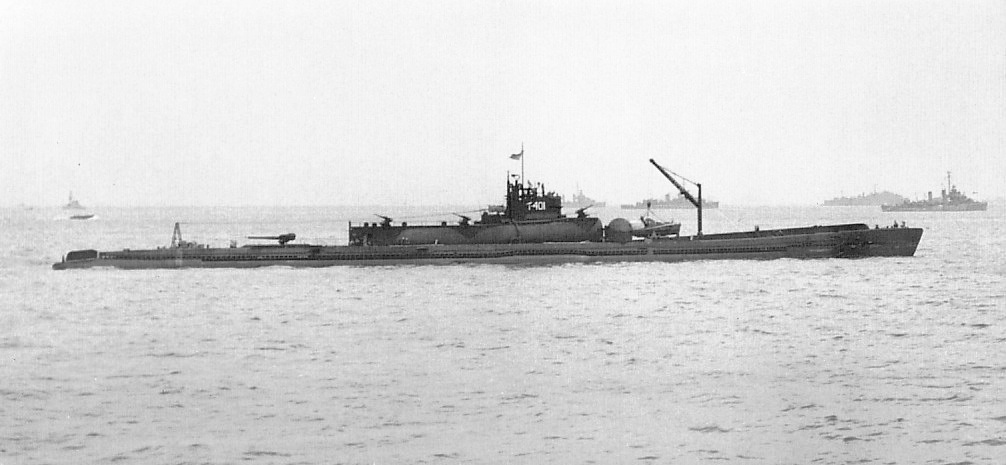

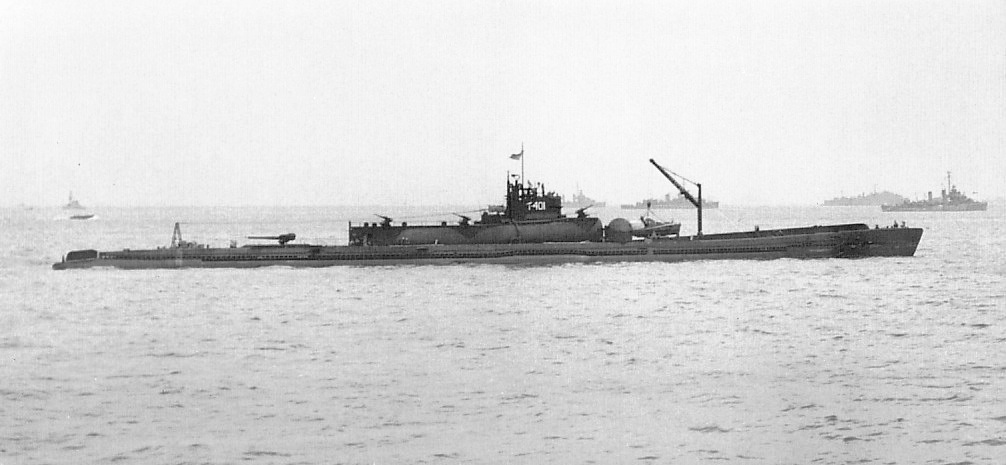

Japan had the most varied fleet of submarines of

Japan had the most varied fleet of submarines of

John Holland

German Submarines of WWII

Submarine Simulations

- German Midget Submarine

- German Midget Submarine

Developed for the NOVA television series.

Role of the Modern Submarine

Submariners of WWII

— World War II Submarine Veterans History Project

German U-Boats 1935–1945

U.S. ship photo archive

The Sub Report

by Graham Hawkes

''Submarines, the Enemy Unseen'', History Today

* American Society of Safety Engineers. Journal of Professional Safety. ''Submarine Accidents: A 60-Year Statistical Assessment''. C. Tingle. September 2009. pp. 31–39. Ordering full article: https://www.asse.org/professionalsafety/indexes/2009.php; or Reproduction fewer graphics/tables: http://www.allbusiness.com/government/government-bodies-offices-government/12939133-1.html. {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Submarines Maritime history, Submarine Submarines History of technology, Submarines Dutch inventions

under the sea

"Under the Sea" is a song from The Walt Disney Company, Disney's 1989 animation, animated film ''The Little Mermaid (1989 film), The Little Mermaid'', composed by Alan Menken with lyrics by Howard Ashman. It is influenced by the Calypso music, c ...

. Humanity has employed a variety of methods to travel underwater for exploration, recreation, research and significantly warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular ...

. While early attempts, such as those by Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

, were rudimentary, the advent of new propulsion systems, fuels, and sonar

Sonar (sound navigation and ranging or sonic navigation and ranging) is a technique that uses sound propagation (usually underwater, as in submarine navigation) to navigation, navigate, measure distances (ranging), communicate with or detect o ...

, propelled an increase in submarine technology. The introduction of the diesel engine

The diesel engine, named after Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which ignition of the fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to mechanical compression; thus, the diesel engine is a so-call ...

, then the nuclear submarine

A nuclear submarine is a submarine powered by a nuclear reactor, but not necessarily nuclear-armed. Nuclear submarines have considerable performance advantages over "conventional" (typically diesel-electric) submarines. Nuclear propulsion, ...

, saw great expansion in submarine use - and specifically military use - during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, and the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. The Second World War use of the U-Boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare role ...

by the German Navy

The German Navy (, ) is the navy of Germany and part of the unified ''Bundeswehr'' (Federal Defense), the German Armed Forces. The German Navy was originally known as the ''Bundesmarine'' (Federal Navy) from 1956 to 1995, when ''Deutsche Mari ...

against the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

and commercial shipping, and the Cold War's use of submarines by the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and Russia, helped solidify the submarine's place in popular culture

Popular culture (also called mass culture or pop culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as, popular art or mass art) and objects that are dominant or prevalent in a ...

. The latter conflicts also saw an increasing role for the military submarine as a tool of subterfuge, hidden warfare, and nuclear deterrent

Nuclear strategy involves the development of doctrines and strategies for the production and use of nuclear weapons.

As a sub-branch of military strategy, nuclear strategy attempts to match nuclear weapons as means to political ends. In additi ...

. The military use of submarines continues to this day, predominantly by North Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu River, Y ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, the United States and Russia.

Beyond their use in warfare, submarines continue to have recreational and scientific uses. They are heavily employed in the exploration of the sea bed, and the deepest places of the ocean floor. They are used extensively in search and rescue operations for other submarines, surface vessels, and air craft, and offer a means to descend vast depths beyond the reach of scuba diving

Scuba diving is a mode of underwater diving whereby divers use breathing equipment that is completely independent of a surface air supply. The name "scuba", an acronym for "Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus", was coined by Chris ...

for both exploration and recreation. They remains a focus of popular culture and the subject of numerous books and films.

Early

siege of Tyre (332 BC)

The Siege of Tyre was orchestrated by Alexander the Great in 332 BC during his campaigns against the Persians. The Macedonian army was unable to capture the city, which was a strategic coastal base on the Mediterranean Sea, through convention ...

, Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

used divers, according to Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

. Later legends suggested that Alexander descended into the sea using a primitive submersible

A submersible is a small watercraft designed to operate underwater. The term "submersible" is often used to differentiate from other underwater vessels known as submarines, in that a submarine is a fully self-sufficient craft, capable of ind ...

in the form of a diving bell

A diving bell is a rigid chamber used to transport divers from the surface to depth and back in open water, usually for the purpose of performing underwater work. The most common types are the open-bottomed wet bell and the closed bell, which c ...

, as depicted in a 16th-century illustration in the works of the Mughal poet Amir Khusrau

Abu'l Hasan Yamīn ud-Dīn Khusrau (1253–1325 AD), better known as Amīr Khusrau was an Indo-Persian culture, Indo-Persian Sufi singer, musician, poet and scholar who lived under the Delhi Sultanate. He is an iconic figure in the cultural his ...

.

According to a report attributed to Tahbir al-Tayseer in ''Opusculum Taisnieri'' published in 1562:

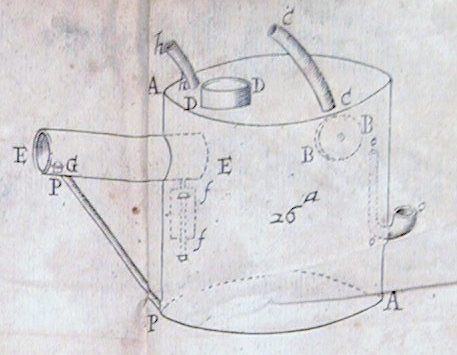

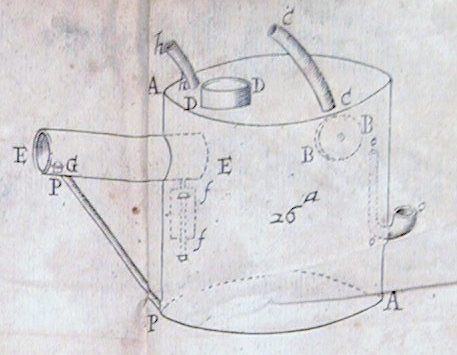

Although there were various plans for submersibles or submarines during the

Although there were various plans for submersibles or submarines during the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, the Englishman William Bourne designed one of the prototype submarines in 1578. This was to be a completely enclosed boat that could be submerged and rowed beneath the surface. Comprising a completely enclosed wooden vessel sheathed in waterproofed leather, it was to be submerged by using hand-operated wooden screw thread

A screw thread, often shortened to thread, is a helical structure used to convert between rotational and linear movement or force. A screw thread is a ridge wrapped around a cylinder or cone in the form of a helix, with the former being called a ...

adjustable plunger

A plunger, force cup, plumber's friend or plumber's helper is a tool used to clear blockages in drains and pipes. It consists of a rubber suction cup attached to a stick (''shaft'') usually made of wood or plastic. A different bellows-like desi ...

s pressing against flexible leather bags located at the sides to increase or decrease the volume of water to adjust the buoyancy of the craft. The sketch (left) suggests that the depth adjustment was utilizing a crankset

The crankset (in the US) or chainset (in the UK), is the component of a bicycle drivetrain that converts the reciprocating motion of the rider's legs into rotational motion used to drive the chain or belt, which in turn drives the rear wheel. ...

projecting above the surface. There is no obvious accommodation for crew.

In 1596 the Scottish mathematician and theologian John Napier

John Napier of Merchiston (; 1 February 1550 – 4 April 1617), nicknamed Marvellous Merchiston, was a Scottish landowner known as a mathematician, physicist, and astronomer. He was the 8th Laird of Merchiston. His Latinized name was Ioann ...

wrote in his ''Secret Inventions'' the following: "These inventions besides devises of sayling under water with divers, other devises and strategems for harming of the enemyes by the Grace of God and worke of expert Craftsmen I hope to perform."

It is unclear whether or not Napier ever carried out his plans. Henry Briggs Henry Briggs may refer to:

*Henry Briggs (mathematician) (1561–1630), English mathematician

*Henry Perronet Briggs (1793–1844), English painter

*Henry George Briggs (1824–1872), English merchant, traveller, and orientalist

*Henry Shaw Briggs ...

, who was professor of mathematics at Gresham College, London, and later at Oxford, was a friend of Napier, whom he visited in 1615 and 1616, and was also an acquaintance of Cornelius Van Drebbel, a Dutchman in the service of James I of England

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland as James I from the Union of the Crowns, union of the Scottish and Eng ...

, who designed and built the first successful submarine in 1620. Hence, it is not impossible that it was because of the interest taken by Napier in the submarine that Briggs came in touch with Drebbel.

Drebbel's submarine was propelled by oars. The precise nature of this submarine is unclear, it may be possible that it resembled a bell towed by a boat. Two improved types were tested in the

Drebbel's submarine was propelled by oars. The precise nature of this submarine is unclear, it may be possible that it resembled a bell towed by a boat. Two improved types were tested in the River Thames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the The Isis, River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the Longest rivers of the United Kingdom, se ...

between 1620 and 1624. Of one of these tests Constantijn Huygens

Sir Constantijn Huygens, Lord of Zuilichem ( , , ; 4 September 159628 March 1687), was a Dutch Golden Age poet and composer. He was also secretary to two Princes of Orange: Frederick Henry and William II, and the father of the scientist C ...

reports in his autobiography of 1651 the following:

On 18 October 1690, his son Constantijn Huygens, Jr.

Constantijn Huygens Jr., Lord of Zuilichem (10 March 1628 – October 1697), was a Dutch statesman and poet, mostly known for his work on scientific instruments (sometimes together with his younger brother Christiaan Huygens). But, he was also a ...

commented in his diary on how Drebbel was able to measure the depth to which his boat had descended (which was necessary to prevent the boat from sinking) utilizing a quicksilver barometer:

In order to solve the problem of the absence of oxygen, Drebbel was able to create oxygen out of saltpetre

Potassium nitrate is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . This alkali metal nitrate salt is also known as Indian saltpetre (large deposits of which were historically mined in India). It is an ionic salt of potassium ions K+ and nitra ...

to refresh the air in his submarine. An indication of this can be found in Drebbel's own work: ''On the Nature of the Elements'' (1604), in the fifth chapter:

The introduction of Drebbel's submarine concept seemed beyond conventional expectations of what science was thought to have been capable of at the time. Commenting on the scientific basis of Drebbel's claims, renowned German astronomer Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

was said to have remarked in 1607: "If rebbelcan create a new spirit, by means of which he can move and keep in motion his instrument without weights or propelling power, he will be Apollo in my opinion."

Although the first submersible vehicles were tools for exploring underwater, it did not take long for inventors to recognize their military potential. The strategic advantages of submarines were first set out by Bishop John Wilkins

John Wilkins, (14 February 1614 – 19 November 1672) was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher, and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

Wilkins is one of the fe ...

of Chester

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Loca ...

in ''Mathematical Magick

''Mathematical Magick'' (complete title: ''Mathematical Magick, or, The wonders that may by performed by mechanical geometry''.) is a treatise by the English clergyman, natural philosopher, polymath and author John Wilkins (1614 – 1672). It wa ...

'' in 1648:

Between 1690 and 1692, the French physicist

Between 1690 and 1692, the French physicist Denis Papin

Denis Papin FRS (; 22 August 1647 – 26 August 1713) was a French physicist, mathematician and inventor, best known for his pioneering invention of the steam digester, the forerunner of the pressure cooker and of the steam engine.

Early lif ...

designed and built two submarines. The first design (1690) was a strong and heavy metallic square box, equipped with an efficient pump

A pump is a device that moves fluids (liquids or gases), or sometimes slurries, by mechanical action, typically converted from electrical energy into hydraulic energy. Pumps can be classified into three major groups according to the method they u ...

that pumped air into the hull to raise the inner pressure. When the air pressure reached the required level, holes were opened to let in some water. This first machine was destroyed by accident. The second design (1692) had an oval shape and worked on similar principles. A water pump controlled the buoyancy of the machine. According to some sources, a spy of German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathema ...

called Haes reported that Papin had met with some success with his second design on the River Lahn

The Lahn is a , right (or eastern) tributary of the Rhine in Germany. Its course passes through the States of Germany, federal states of North Rhine-Westphalia (23.0 km), Hesse (165.6 km), and Rhineland-Palatinate (57.0 km).

It ...

.

By the mid 18th century, over a dozen patents for submarines/submersible boats had been granted in England. In 1747, Nathaniel Symons patented and built the first known working example of the use of a ballast tank for submersion. His design used leather bags that could fill with water to submerge the craft. A mechanism was used to twist the water out of the bags and cause the boat to resurface. In 1749, the Gentlemen's Magazine

''The Gentleman's Magazine'' was a monthly magazine founded in London, England, by Edward Cave in January 1731. It ran uninterrupted for almost 200 years, until 1922. It was the first to use the term ''magazine'' (from the French ''magazine'' ...

reported that a similar design had been proposed by Giovanni Borelli

Giovanni Alfonso Borelli (; 28 January 1608 – 31 December 1679) was a Renaissance Italian physiologist, physicist, and mathematician. He contributed to the modern principle of scientific investigation by continuing Galileo's practice of testi ...

in 1680. By this point of development, further improvement in design stagnated for over a century, until new industrial technologies for propulsion and stability could be applied.

Early modern

The carpenter Yefim Nikonov built the first military submarine in 1720 by order of TsarPeter the Great

Peter I ( – ), most commonly known as Peter the Great,) or Pyotr Alekséyevich ( rus, Пётр Алексе́евич, p=ˈpʲɵtr ɐlʲɪˈksʲejɪvʲɪtɕ, , group=pron was a Russian monarch who ruled the Tsardom of Russia from t ...

in Russia. Nikonov armed his submarine with "fire tubes", weapons akin to flame-throwers. The submarine was designed to approach an enemy vessel, put the ends of the "tubes" out of the water, and blow up the ship with a combustible mixture. In addition, Nikonov designed an airlock for aquanauts to come out of the submarine and to destroy the bilge of the ship. With the death of Peter I in January 1725, Nikonov lost his principal patron and the Admiralty withdrew support for the project.

The first American military submarine was in 1776, a hand-powered egg-shaped (or acorn-shaped) device designed by the American

The first American military submarine was in 1776, a hand-powered egg-shaped (or acorn-shaped) device designed by the American David Bushnell

David Bushnell (August 30, 1740 – 1824 or 1826), of Westbrook, Connecticut, was an American inventor, a patriot, one of the first American combat engineers, a teacher, and a medical doctor.

Bushnell invented the first submarine to be used in ...

, to accommodate a single man. It was the first submarine capable of independent underwater operation and movement, and the first to use screws

A screw and a bolt (see '' Differentiation between bolt and screw'' below) are similar types of fastener typically made of metal and characterized by a helical ridge, called a ''male thread'' (external thread). Screws and bolts are used to fa ...

for propulsion. However, according to British naval historian Richard Compton-Hall, the problems of achieving neutral buoyancy would have rendered the vertical propeller of the ''Turtle'' useless. The route that ''Turtle'' had to take to attack its intended target, , was slightly across the tidal stream which would, in all probability, have resulted in Ezra Lee becoming exhausted.Compton-Hall, pp. 32–40 There are also no British records of an attack by a submarine during the war. In the face of these and other problems, Compton-Hall suggests that the entire story around the ''Turtle'' was fabricated as disinformation and morale-boosting propaganda, and that if Ezra Lee did carry out an attack, it was in a covered rowing boat rather than in ''Turtle''. Replicas of ''Turtle'' have been built to test the design. One replica (''Acorn''), constructed by Duke Riley

Duke Riley is an American artist. Riley earned a BFA in painting from the Rhode Island School of Design, and a MFA in Sculpture from the Pratt Institute. He lives in Brooklyn, New York. He is noted for a body of work incorporating the seafarer ...

and Jesse Bushnell (claiming to be a descendant of David Bushnell

David Bushnell (August 30, 1740 – 1824 or 1826), of Westbrook, Connecticut, was an American inventor, a patriot, one of the first American combat engineers, a teacher, and a medical doctor.

Bushnell invented the first submarine to be used in ...

), used the tide to get within of the in New York City (a police boat stopped ''Acorn'' for violating a security zone).

Displays of replicas of ''Turtle'' which acknowledge its place in history appear in the Connecticut River Museum

The Connecticut River Museum is a U.S. educational and cultural institution based at Steamboat Dock in Essex, Connecticut that focuses on the marine environment and maritime heritage of the Connecticut River Valley.

The three-story Connecticut R ...

, the U.S. Navy's Submarine Force Library and Museum

The United States Navy Submarine Force Library and Museum is located on the Thames River in Groton, Connecticut. It is the only submarine museum managed exclusively by the Naval History & Heritage Command division of the Navy, and this makes it a ...

, Britain's Royal Navy Submarine Museum

The Royal Navy Submarine Museum at Gosport is a maritime museum tracing the international history of submarine development from the age of Alexander the Great to the present day, and particularly the history of the Royal Navy Submarine Service ...

and Monaco's Oceanographic Museum

The Oceanographic Museum (''Musée océanographique'') is a museum of marine sciences in Monaco-Ville, Monaco.

This building is part of the Institut océanographique, which is committed to sharing its knowledge of the oceans.

History

The ...

.

In 1800, the

In 1800, the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

built a human-powered submarine designed by Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton (November 14, 1765 – February 24, 1815) was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing the world's first commercially successful steamboat, the (also known as ''Clermont''). In 1807, that steamboat ...

, the . It also had a sail for use on the surface and so exhibited the first known use of dual propulsion on a submarine. It proved capable of using mines to destroy two warships during demonstrations. The French eventually gave up on the experiment in 1804, as did the British, when Fulton later offered them the submarine design.

In 1834 the Russian Army General demonstrated the first rocket-equipped submarine to Emperor Nicholas I.

The ''Submarino Hipopótamo'', the first submarine built in South America, underwent testing in Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ''Eku ...

on September 18, 1837. Its designer, Jose Rodriguez Lavandera, successfully crossed the Guayas River

The Guayas River also called Rio Guayas is a major river in western Ecuador. It gives name to Guayas Province and is the most important river in South America that does not flow into the Atlantic Ocean or any of its marginal seas. Its total lengt ...

in Guayaquil

, motto = Por Guayaquil Independiente en, For Independent Guayaquil

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Ecuador#South America

, pushpin_re ...

accompanied by Jose Quevedo. Rodriguez Lavandera had enrolled in the Ecuadorian Navy in 1823, becoming a Lieutenant by 1830. The ''Hipopotamo'' crossed the Guayas on two more occasions, but it was abandoned because of lack of funding and interest from the government.

In 1851 a Bavarian artillery corporal, Wilhelm Bauer

Wilhelm Bauer (23 December 1822 – 20 June 1875) was a German inventor and engineer who built several hand-powered submarines.

Biography

Wilhelm Bauer was born in Dillingen an der Donau, Dillingen in the Kingdom of Bavaria. His father was a ...

, took a submarine designed by him called the ''Brandtaucher

''Brandtaucher'' (German for ''Fire-diver'') was a submersible designed by the Bavarian inventor and engineer Wilhelm Bauer and built by Schweffel & Howaldt in Kiel for Schleswig-Holstein's Flotilla (part of the ''Reichsflotte'') in 1850. Th ...

'' (fire-diver) to sea in Kiel Harbour. Built by August Howaldt

August Ferdinand Howaldt (23 October 1809 – 4 August 1883) was a German engineer and ship builder. The German sculptor Georg Ferdinand Howaldt was his brother.

Biography

Born in Braunschweig, the son of the silversmith David Ferdinand Howal ...

and powered by a treadwheel

A treadwheel, or treadmill, is a form of engine typically powered by humans. It may resemble a water wheel in appearance, and can be worked either by a human treading paddles set into its circumference (treadmill), or by a human or animal standing ...

, ''Brandtaucher'' sank, but the crew of three managed to escape.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

both sides made use of submarines. Examples were the , for the Union, and the ''Hunley'', for the Confederacy. The ''Hunley'' was the first submarine to successfully attack and sink an opposing warship. (see below

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

*Bottom (disambiguation)

Bottom may refer to:

Anatomy and sex

* Bottom (BDSM), the partner in a BDSM who takes the passive, receiving, or obedient role, to that of the top or ...

)

In 1863 the was built by the

In 1863 the was built by the German American

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the l ...

Julius H. Kroehl

Julius Hermann Kroehl (in German, ''Kröhl'') (1820 – September 9, 1867) was a German American inventor and engineer. He invented and built the first submarine able to dive and resurface on its own, the Sub Marine Explorer, technically adv ...

, and featured a pressurized work chamber for the crew to exit and enter underwater. This pre-figured modern diving arrangements such as the lock-out dive chamber, though the problems of decompression sickness

Decompression sickness (abbreviated DCS; also called divers' disease, the bends, aerobullosis, and caisson disease) is a medical condition caused by dissolved gases emerging from solution as bubbles inside the body tissues during decompressio ...

were not well understood at the time. After its public maiden dive in 1866, the ''Sub Marine Explorer'' was used for pearl diving off the coast of Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cos ...

. It was capable of diving deeper than , deeper than any other submarine built before.

The Chilean government commissioned the in 1865, during the Chincha Islands War

The Chincha Islands War, also known as Spanish–South American War ( es, Guerra hispano-sudamericana), was a series of coastal and naval battles between Spain and its former colonies of Peru, Chile, Ecuador, and Bolivia from 1865 to 1879. The ...

(1864–1866) when Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

and Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

fought against Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

. Built by the German engineer Karl Flach

Karl Flach (Villmar, 15 August 1821 - Bay of Valparaiso, 3 May 1866 ) was a German mechanic and engineer who designed and built the Flach (submarine), Flach; the first Chilean submarine.

Biography

Born Johann Anton Flach, he was the son of watc ...

, the submarine sank during tests in Valparaiso Bay on May 3, 1866, with the entire eleven-man crew.

During the War of the Pacific

The War of the Pacific ( es, link=no, Guerra del Pacífico), also known as the Saltpeter War ( es, link=no, Guerra del salitre) and by multiple other names, was a war between Chile and a Bolivian–Peruvian alliance from 1879 to 1884. Fought ...

in 1879, the Peruvian government commissioned and built a submarine, the ''Toro Submarino

''Toro Submarino'' (lit. "Submarine Bull") was a Peruvian submarine developed during the War of the Pacific in 1879. It is considered the first operational submarine or submersible in Latin America. Being fully operational, waiting for its oppo ...

'' design by the Peruvian engineer Federico Blume and built in Paita

Paita is a city in northwestern Peru. It is the capital of the Paita Province which is in the Piura Region. It is a leading seaport in the region. Paita is located 1,089 km northwest of the country's capital Lima, and 57 km northwest of ...

, Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

. It is considered the first operational submarine or submersible in Latin America

Latin America or

* french: Amérique Latine, link=no

* ht, Amerik Latin, link=no

* pt, América Latina, link=no, name=a, sometimes referred to as LatAm is a large cultural region in the Americas where Romance languages — languages derived f ...

. With 48 feet long (15 meters) and manually operate by a crew of 11 persons, it could sumerge to a depth of 12 ft (3.7 m) with a ventilation system a speed of 3 knots (5.6 km/h; 3.5 mph) and a maximum dive of 72 feet (22 meters). Being fully operational, waiting for its opportunity to attack with naval mines

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive device placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Unlike depth charges, mines are deposited and left to wait until they are triggered by the approach of, or contact with, any v ...

during the Blockade of Callao

The Blockade of Callao was a military operation that occurred during the War of the Pacific or the Salitre War and that consisted of the Chilean squadron preventing the entry of ships to the port of Callao and the neighboring coves between 10 A ...

, it was scuttled to avoid its capture by Chilean troops on January 17, 1881, before the imminent occupation of Lima.

Mechanical power

The first submarine that did not rely on human power for propulsion was the

The first submarine that did not rely on human power for propulsion was the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

submarine ''Plongeur

Plongeur, the French word for '' diver'' may refer to the following

*The French submarine ''Plongeur''

*An employee charged with washing dishes

Dishwashing, washing the dishes, doing the dishes, or washing up in Great Britain, is the proces ...

'', launched in 1863, and equipped with a reciprocating engine using compressed air from 23 tanks at . In practice, the submarine was virtually unmanageable underwater, with very poor speed and maneouverability.

The first air independent and

The first air independent and combustion

Combustion, or burning, is a high-temperature exothermic redox chemical reaction between a fuel (the reductant) and an oxidant, usually atmospheric oxygen, that produces oxidized, often gaseous products, in a mixture termed as smoke. Combusti ...

powered submarine was the '' Ictineo II'', designed by the Catalan engineer Narcís Monturiol

Narcís Monturiol i Estarriol (; Narciso Monturiol Estarriol, in Spanish, 28 September 1819 – 6 September 1885) was a Spanish inventor, artist and engineer born in Figueres, Catalonia, Spain. He was the inventor of the first air-independent an ...

. Originally launched in 1864 as a human-powered vessel, propelled by 16 men, it was converted to peroxide propulsion and steam in 1867. The craft was designed for a crew of two, could dive to , and demonstrated dives of two hours. On the surface, it ran on a steam engine, but underwater such an engine would quickly consume the submarine's oxygen. To solve this problem, Monturiol invented an air-independent propulsion

Air-independent propulsion (AIP), or air-independent power, is any marine propulsion technology that allows a non-nuclear submarine to operate without access to atmospheric oxygen (by surfacing or using a snorkel). AIP can augment or replace the ...

system. As the air-independent power system drove the screw, the chemical process driving it also released oxygen into the hull for the crew and an auxiliary steam engine. Apart from being mechanically powered, Monturiol's pioneering double-hulled vessels also solved pressure, buoyancy, stability, diving and ascending problems that earlier designs had encountered.

The submarine became a potentially viable weapon with the development of the first practical self-propelled torpedoes. The Whitehead torpedo

The Whitehead torpedo was the first self-propelled or "locomotive" torpedo ever developed. It was perfected in 1866 by Robert Whitehead from a rough design conceived by Giovanni Luppis of the Austro-Hungarian Navy in Fiume. It was driven by a th ...

was the first such weapon, and was designed in 1866 by British engineer Robert Whitehead

Robert Whitehead (3 January 1823 – 14 November 1905) was an English engineer who was most famous for developing the first effective self-propelled naval torpedo.

Early life

He was born in Bolton, England, the son of James Whitehead, ...

. His 'mine ship' was an long, diameter torpedo propelled by compressed air

Compressed air is air kept under a pressure that is greater than atmospheric pressure. Compressed air is an important medium for transfer of energy in industrial processes, and is used for power tools such as air hammers, drills, wrenches, and o ...

and carried an explosive warhead

A warhead is the forward section of a device that contains the explosive agent or toxic (biological, chemical, or nuclear) material that is delivered by a missile, rocket, torpedo, or bomb.

Classification

Types of warheads include:

* Explosiv ...

. The device had a speed of and could hit a target away. Many naval services procured the Whitehead torpedo during the 1870s and it first proved itself in combat during the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars (or Ottoman–Russian wars) were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European histor ...

when, on 16 January 1878, the Turkish ship ''Intibah'' was sunk by Russian

Russian(s) refers to anything related to Russia, including:

*Russians (, ''russkiye''), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*Rossiyane (), Russian language term for all citizens and peo ...

torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of se ...

s carrying Whiteheads.

During the 1870s and 1880s, the basic contours of the modern submarine began to emerge, through the inventions of the English inventor and curate, George Garrett, and his industrialist financier Thorsten Nordenfelt

Thorsten Nordenfelt (1 March 1842 – 8 February 1920), was a Swedish inventor and industrialist.

Career

Nordenfelt was born in Örby outside Kinna, Sweden, the son of a colonel. The surname was and is often spelled Nordenfeldt, though Thorsten ...

, and the Irish inventor John Philip Holland

John Philip Holland ( ga, Seán Pilib Ó hUallacháin/Ó Maolchalann) (24 February 184112 August 1914) was an Irish engineer who developed the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the US Navy, and the first Royal Navy submarine, ''Hol ...

.

In 1878, Garrett built a long hand-cranked submarine of about 4.5 tons, which he named the ''Resurgam

''Resurgam'' (Latin: ''"I shall rise again"'') is the name given to an early Victorian submarine and its prototype, designed and built in Britain by Reverend George Garrett. She was intended as a weapon to penetrate the chain netting placed ...

''. This was followed by the second (and more famous) ''Resurgam

''Resurgam'' (Latin: ''"I shall rise again"'') is the name given to an early Victorian submarine and its prototype, designed and built in Britain by Reverend George Garrett. She was intended as a weapon to penetrate the chain netting placed ...

'' of 1879, built by Cochran & Co. at Birkenhead

Birkenhead (; cy, Penbedw) is a town in the Metropolitan Borough of Wirral, Merseyside, England; historically, it was part of Cheshire until 1974. The town is on the Wirral Peninsula, along the south bank of the River Mersey, opposite Liver ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

. The construction was of iron plates fastened to iron frames, with the central section of the vessel clad with wood secured by iron straps. As built, it was long by in diameter, weighed , and had a crew of 3. ''Resurgam

''Resurgam'' (Latin: ''"I shall rise again"'') is the name given to an early Victorian submarine and its prototype, designed and built in Britain by Reverend George Garrett. She was intended as a weapon to penetrate the chain netting placed ...

'' was powered by a closed cycle steam engine, which provided enough steam to turn the single propeller for up to 4 hours. It was designed to have positive buoyancy, and diving was controlled by a pair of hydroplanes amidships. At the time it cost £1,538.

Although his design was not very practical – the steam boiler generated intense heat in the cramped confines of the vessel, and it lacked longitudinal stability – it caught the attention of the Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

industrialist Thorsten Nordenfelt

Thorsten Nordenfelt (1 March 1842 – 8 February 1920), was a Swedish inventor and industrialist.

Career

Nordenfelt was born in Örby outside Kinna, Sweden, the son of a colonel. The surname was and is often spelled Nordenfeldt, though Thorsten ...

. Discussions between the two led to the first practical steam-powered submarines, armed with torpedoes and ready for military use.

The first such boat was the ''Nordenfelt I'', a 56 tonne, vessel similar to Garret's ill-fated ''

The first such boat was the ''Nordenfelt I'', a 56 tonne, vessel similar to Garret's ill-fated ''Resurgam

''Resurgam'' (Latin: ''"I shall rise again"'') is the name given to an early Victorian submarine and its prototype, designed and built in Britain by Reverend George Garrett. She was intended as a weapon to penetrate the chain netting placed ...

'', with a range of , armed with a single torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, and with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, su ...

, in 1885. Like ''Resurgam'', ''Nordenfelt I'' operated on the surface by steam, then shut down its engine to dive. While submerged, the submarine released pressure generated when the engine was running on the surface to provide propulsion for some distance underwater. Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

, fearful of the return of the Ottomans

The Ottoman Turks ( tr, Osmanlı Türkleri), were the Turkic founding and sociopolitically the most dominant ethnic group of the Ottoman Empire ( 1299/1302–1922).

Reliable information about the early history of Ottoman Turks remains scarce, ...

, purchased it. Nordenfelt commissioned the Barrow Shipyard in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

in 1886 to build ''Nordenfelt II'' () and ''Nordenfelt III'' (''Abdül Mecid'') in 1887. They were powered by a coal-fired Lamm steam engine turning a single screw, and carried two 356mm torpedo tubes and two 35mm machine guns. They were loaded with a total of 8 tons of coal as fuel and could dive to a depth of . It was 30.5m long and 6m wide, and weighed 100 tons. It carried a normal crew of 7. It had a maximum surface speed of , and a maximum speed of while submerged. ''Abdülhamid'' became the first submarine in history to fire a torpedo submerged.

Nordenfelt's efforts culminated in 1887 with ''Nordenfelt IV'', which had twin motors and twin torpedoes. It was sold to the Russians, but soon ran aground and was scrapped. Garrett and Nordenfelt made significant advances in constructing the first modern, militarily capable submarines and fired up military and popular interest around the world for this new technology. However, the solution to fundamental technical problems, such as propulsion, quick submergence, and the maintenance of balance underwater was still lacking, and would only be solved in the 1890s.

Electric power

A reliable means of propulsion for submerged vessels was only made possible in the 1880s with the advent of the necessary electric battery technology. The first electrically powered submarines were built by the Polish engineerStefan Drzewiecki

Stefan Drzewiecki (russian: Джеве́цкий Степа́н Ка́рлович (Казими́рович); 26 July 1844, Kunka, Podolia, Russian Empire (today Ukraine) – 23 April 1938, Paris) was a Polish scientist, journalist, engineer, con ...

in 1881, he designed and constructed the world’s first submarine in Russia, and later other engineers used his design in their constructions, they were James Franklin Waddington and the team of James Ash and Andrew Campbell in England, Dupuy de Lôme and Gustave Zédé in France and Isaac Peral

Isaac Peral y Caballero (1 June 1851, in Cartagena – 22 May 1895, in Berlin), was a Spanish engineer, naval officer and designer of the Peral Submarine. He joined the Spanish navy in 1866, and developed the first electric-powered submarine whi ...

in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

.

In 1884, Drzewiecki converted 2 mechanical submarines, installing in each a engine with a new, at the time, source of energy – batteries. In tests, the submarines travelled under the water against the flow of the Neva River at a rate of . They were the first submarines in the world with electric propulsion. Ash and Campbell constructed their craft, the ''Nautilus'', in 1886. It was long with a engine powered by 52 batteries. It was an advanced design for the time, but became stuck in the mud during trials and was discontinued. Waddington's ''Porpoise'' vessel showed more promise. Waddington had formerly worked in the shipyard in which Garrett had been active. Waddington's vessel was similar in size to the ''Resurgam

''Resurgam'' (Latin: ''"I shall rise again"'') is the name given to an early Victorian submarine and its prototype, designed and built in Britain by Reverend George Garrett. She was intended as a weapon to penetrate the chain netting placed ...

'' and its propulsion system used 45 accumulator cells with a capacity of 660 ampere hours each. These were coupled in series

Series may refer to:

People with the name

* Caroline Series (born 1951), English mathematician, daughter of George Series

* George Series (1920–1995), English physicist

Arts, entertainment, and media

Music

* Series, the ordered sets used i ...

to a motor

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power gen ...

driving a propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

at about 750 rpm, giving the ship a sustained speed of for at least 8 hours. The boat was armed with two externally mounted torpedoes as well as a mine torpedo that could be detonated electronically. Although the boat performed well in trials, Waddington was unable to attract further contracts and went bankrupt.

Peral Submarine

''Peral'' was the first successful full electric battery-powered submarine, built by the Spanish engineer and sailor Isaac Peral for the Spanish Navy, in Arsenal de la Carraca (today's Navantia). The first fully capable military submarine, she ...

, constructed by Isaac Peral, was launched by the Spanish Navy in the same year, 1888. It had three Schwartzkopff torpedo

The Schwartzkopff torpedo was a torpedo manufactured in the late 19th century by the German firm ''Eisengießerei und Maschinen-Fabrik von L. Schwartzkopff'', later known as Berliner Maschinenbau, based on the Whitehead design. Unlike the Whiteh ...

es 14 in (360 mm) and one torpedo tube in the bow, new air systems, hull shape, propeller, and cruciform external controls anticipating much later designs. ''Peral'' was an all-electrical powered submarine with an underwater speed of 3 kn (5.6 km/h; 3.5 mph). After two years of trials the project was scrapped by naval officialdom who cited, among other reasons, concerns over the range permitted by its batteries.

Many more designs were built at this time by various inventors, but submarines were not put into service by navies until the turn of the 20th century.

Modern

The turn of the 20th century marked a pivotal time in the development of submarines, with a number of important technologies making their debut, as well as the widespread adoption and fielding of submarines by a number of nations.

The turn of the 20th century marked a pivotal time in the development of submarines, with a number of important technologies making their debut, as well as the widespread adoption and fielding of submarines by a number of nations. Diesel electric

Diesel may refer to:

* Diesel engine, an internal combustion engine where ignition is caused by compression

* Diesel fuel, a liquid fuel used in diesel engines

* Diesel locomotive, a railway locomotive in which the prime mover is a diesel engin ...

propulsion would become the dominant power system and instruments such as the periscope would become standardized. Batteries were used for running underwater and gasoline

Gasoline (; ) or petrol (; ) (see ) is a transparent, petroleum-derived flammable liquid that is used primarily as a fuel in most spark-ignited internal combustion engines (also known as petrol engines). It consists mostly of organic co ...

(petrol) or diesel engine

The diesel engine, named after Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which ignition of the fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to mechanical compression; thus, the diesel engine is a so-call ...

s were used on the surface and to recharge the batteries. Early boats used gasoline, but quickly gave way to kerosene

Kerosene, paraffin, or lamp oil is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in aviation as well as households. Its name derives from el, κηρός (''keros'') meaning "wax", and was regi ...

, then diesel, because of reduced flammability. Effective tactics and weaponry were refined in the early part of the century, and the submarine would have a large impact on 20th century warfare.

The Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

inventor John Philip Holland

John Philip Holland ( ga, Seán Pilib Ó hUallacháin/Ó Maolchalann) (24 February 184112 August 1914) was an Irish engineer who developed the first submarine to be formally commissioned by the US Navy, and the first Royal Navy submarine, ''Hol ...

built a model submarine in 1876 and a full scale one in 1878, followed by a number of unsuccessful ones. In 1896, he designed the Holland Type VI submarine. This vessel made use of internal combustion engine power on the surface and electric battery

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

power for submerged operations. Launched on 17 May 1897 at Navy Lt. Lewis Nixon's Crescent Shipyard

Crescent Shipyard, located on Newark Bay in Elizabeth, New Jersey, built a number of ships for the United States Navy and allied nations as well during their production run, which lasted about ten years while under the Crescent name and banner ...

in Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

, New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

, the Holland VI was purchased by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

on 11 April 1900, becoming the United States Navy's first commissioned submarine and renamed USS Holland.

A prototype version of the A-class submarine (''Fulton'') was developed at Crescent Shipyard under the supervision of naval architect and shipbuilder from the United Kingdom, Arthur Leopold Busch

Arthur Leopold Busch or Du Busc (5 March 1866 – 9 March 1956) was a British-born American naval architect responsible for the development of the United States Navy's first submarines.

Biography

Early life

Busch was born in Middlesbrough, North ...

, for the newly reorganized Electric Boat Company

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described ...

in 1900. The ''Fulton'' was never commissioned by the United States Navy and was sold to the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from a ...

in 1905. The submarines were built at two different shipyards on both coasts of the United States. In 1902, Holland received for his relentless pursuit to perfect the modern submarine craft. Many countries became interested in Holland's (weapons) product and purchased the rights to build them during this time.

The Royal Navy commissioned the Holland-class submarine from Vickers

Vickers was a British engineering company that existed from 1828 until 1999. It was formed in Sheffield as a steel foundry by Edward Vickers and his father-in-law, and soon became famous for casting church bells. The company went public in 18 ...

, Barrow-in-Furness

Barrow-in-Furness is a port town in Cumbria, England. Historically in Lancashire, it was incorporated as a municipal borough in 1867 and merged with Dalton-in-Furness Urban District in 1974 to form the Borough of Barrow-in-Furness. In 2023 the ...

, under licence from the Holland Torpedo Boat Company

General Dynamics Electric Boat (GDEB) is a subsidiary of General Dynamics Corporation. It has been the primary builder of submarines for the United States Navy for more than 100 years. The company's main facilities are a shipyard in Groton, C ...

during the years 1901 to 1903. Construction of the boats took longer than anticipated, with the first only ready for a diving trial at sea on 6 April 1902. Although the design had been purchased entirely from the US company, the actual design used was an untested improved version of the original Holland design using a new petrol engine.

Meanwhile, the French steam and electric '' Narval'' was commissioned in June 1900 and introduced the classic double-hull design, with a pressure hull inside the outer shell. These 200-ton ships had a range of over underwater. The French submarine ''Aigrette'' in 1904 further improved the concept by using a diesel rather than a gasoline engine for surface power. Large numbers of these submarines were built, with seventy-six completed before 1914.

By 1914, all the main powers had submarine fleets, though the development of a strategy for their use lay in the future.

At the start of

Meanwhile, the French steam and electric '' Narval'' was commissioned in June 1900 and introduced the classic double-hull design, with a pressure hull inside the outer shell. These 200-ton ships had a range of over underwater. The French submarine ''Aigrette'' in 1904 further improved the concept by using a diesel rather than a gasoline engine for surface power. Large numbers of these submarines were built, with seventy-six completed before 1914.

By 1914, all the main powers had submarine fleets, though the development of a strategy for their use lay in the future.

At the start of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the Royal Navy had the world's largest submarine service by a considerable margin, with 74 boats of the B, C and D classes, of which 15 were oceangoing, with the rest capable of coastal patrols. The D-class, built 1907–1910, were designed to be propelled by diesel motors on the surface to avoid the problems with petrol engines experienced with the A class. These boats were designed for foreign service with an endurance of at on the surface and much-improved living conditions for a larger crew. They were fitted with twin screws for greater maneuverability and with innovative saddle tanks. They were also the first submarines to be equipped with deck guns forward of the conning tower. Armament also included three torpedo tubes (two vertically in the bow and one in the stern). D-class was also the first class of submarine to be equipped with standard wireless transmitters. The aerial was attached to the mast of the conning tower that was lowered before diving. With their enlarged bridge structure, the boat profile was recognisably that of the modern submarine. The D-class submarines were considered to be so innovative that the prototype ''D1'' was built in utmost secrecy in a securely guarded building shed.

The British also experimented with other power sources. Oil-fired steam turbines powered the British "K" class submarines built during the

The British also experimented with other power sources. Oil-fired steam turbines powered the British "K" class submarines built during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

and in following years, but these were not very successful.

The aim was to give them the necessary surface speed to keep up with the British battle fleet.

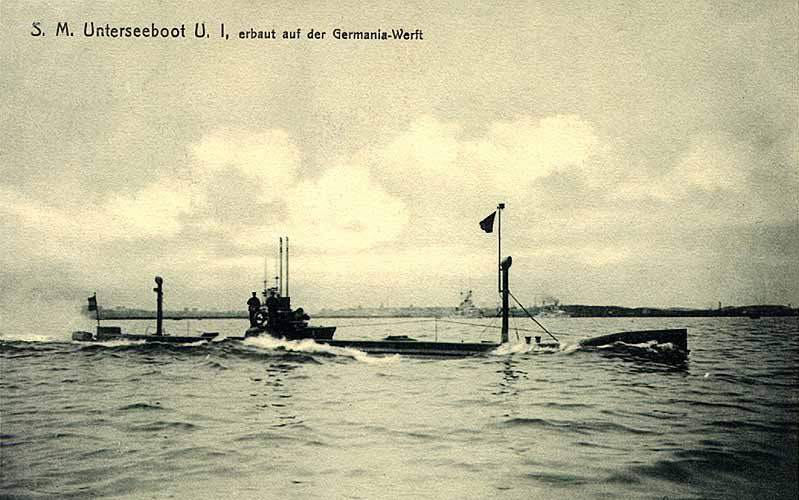

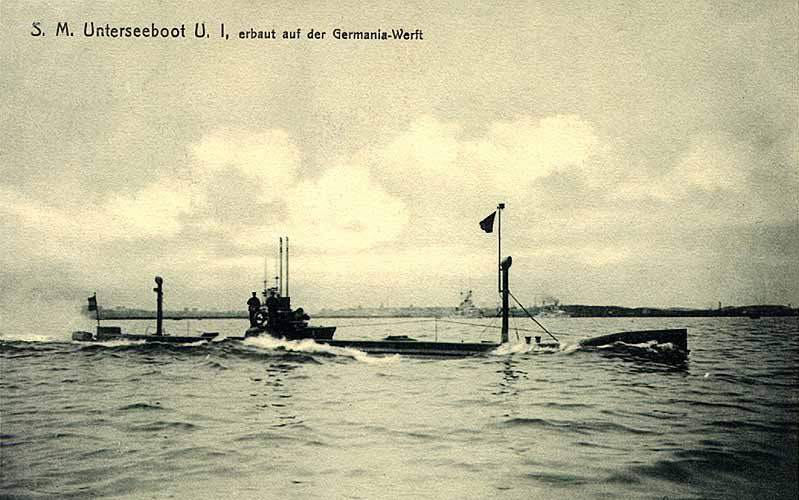

The Germans were slower to recognize the importance of this new weapon. A submersible was initially ordered by the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution of 1917. It developed from a ...

from the Kiel shipyard in 1904, but cancelled after the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

ended. One example was modified and improved, then commissioned into the Imperial German Navy

The Imperial German Navy or the Imperial Navy () was the navy of the German Empire, which existed between 1871 and 1919. It grew out of the small Prussian Navy (from 1867 the North German Federal Navy), which was mainly for coast defence. Wilhel ...

in 1906 as its first U-boat, ''U-1''. It had a double hull, was powered by a Körting kerosene

Kerosene, paraffin, or lamp oil is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in aviation as well as households. Its name derives from el, κηρός (''keros'') meaning "wax", and was regi ...

engine and was armed with a single torpedo tube. The fifty percent larger ''SM U-2'' had two torpedo tubes. A diesel engine

The diesel engine, named after Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which ignition of the fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to mechanical compression; thus, the diesel engine is a so-call ...

was not installed in a German navy boat until the class of 1912–13. At the start of World War I, Germany had 20 submarines of 13 classes in service with more under construction.

Interwar

Diesel submarines needed air to run their engines, and so carried very largebatteries

Battery most often refers to:

* Electric battery, a device that provides electrical power

* Battery (crime), a crime involving unlawful physical contact

Battery may also refer to:

Energy source

*Automotive battery, a device to provide power t ...

for submerged travel. These limited the speed and range of the submarines while submerged.

An early submarine snorkel was designed by James Richardson, an assistant manager at Scotts Shipbuilding and Engineering Company

Scotts Shipbuilding and Engineering Company Limited, often referred to simply as Scotts, was a Scottish shipbuilding company based in Greenock on the River Clyde. In its time in Greenock, Scotts built over 1,250 ships.

History

John Scott fou ...

, Greenock, Scotland, as early as 1916. The snorkel allowed the submarine to avoid detection for long periods by travelling under the water using non-electric powered propulsion. Although the company received a British Patent for the design, no further use was made of it—the British Admiralty did not accept it for use in Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

submarines.

The first German U-boat to be fitted with a snorkel was , which experimented with the equipment in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and from ...

during the summer of 1943. The technology was based on pre-war Dutch experiments with a device named a ''snuiver'' (''sniffer''). As early as 1938, a simple pipe system was installed on the submarines and that enabled them to travel at periscope depth operating on its diesels with almost unlimited underwater range while charging the propulsion batteries. U-boats began to use it operationally in early 1944. By June 1944, about half of the boats stationed in the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

bases were fitted with snorkels.

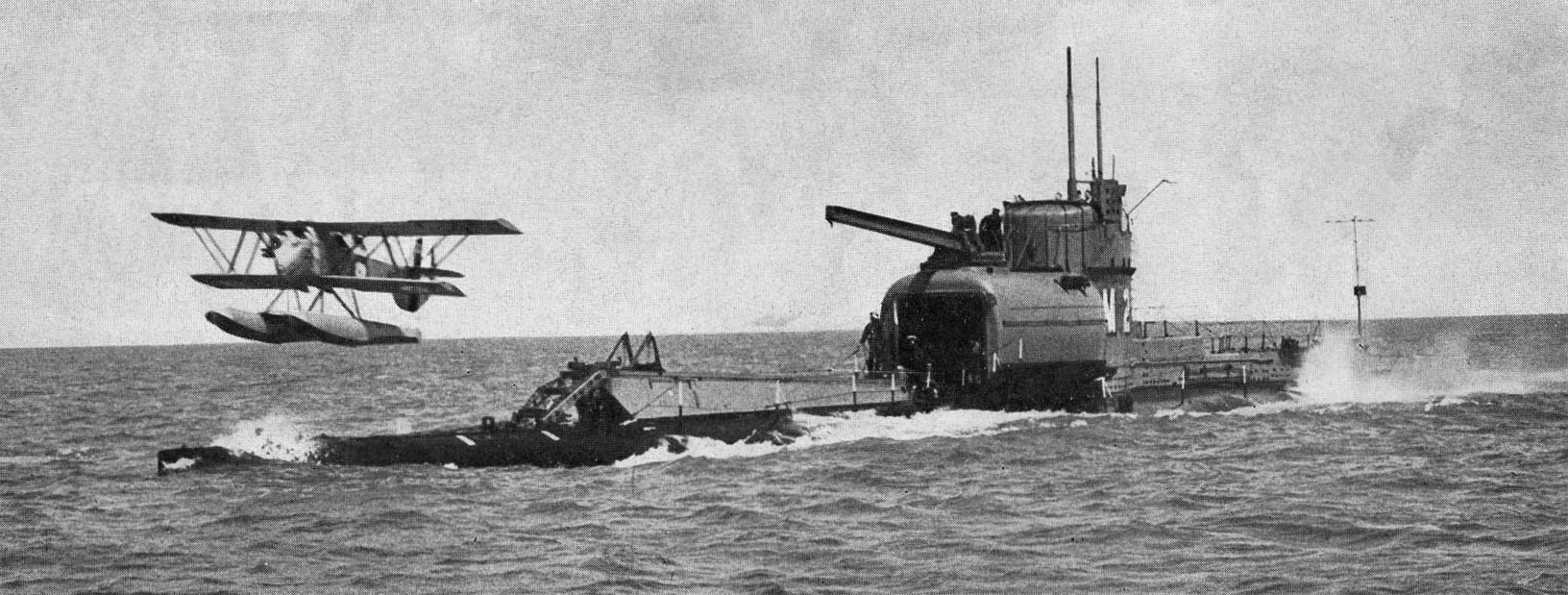

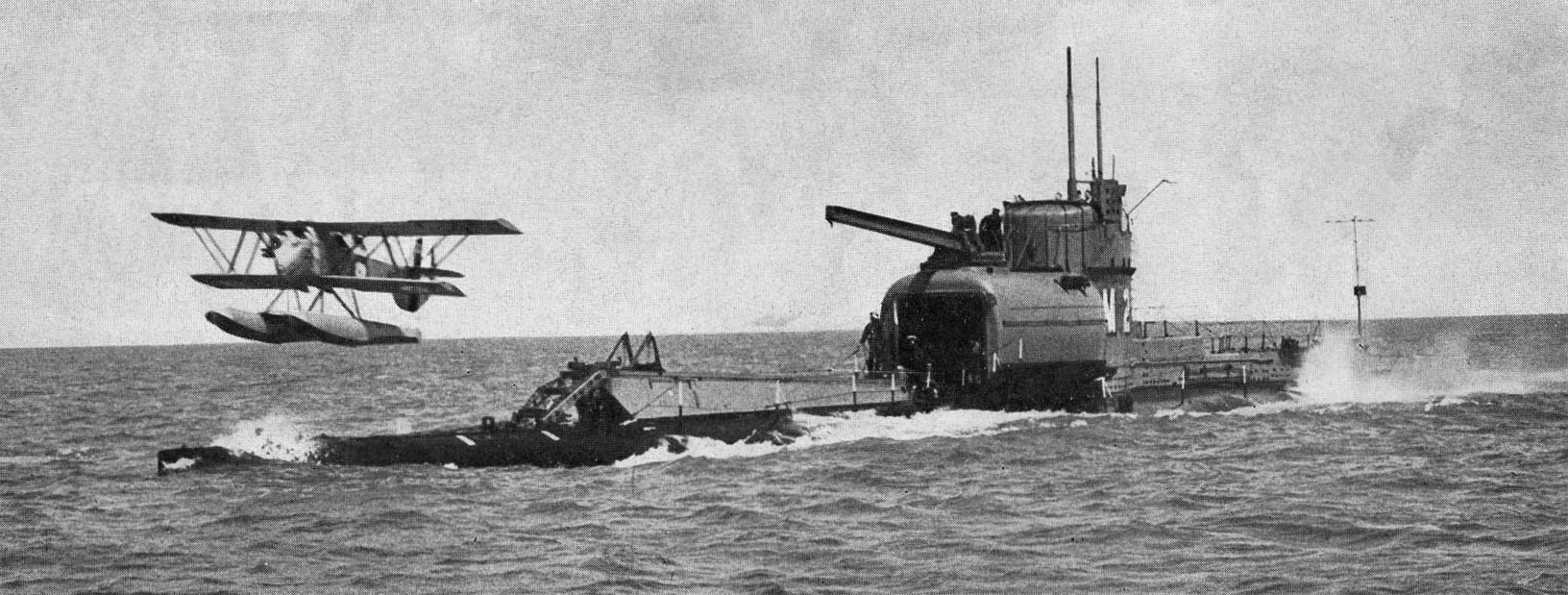

Various new submarine designs were developed during the interwar years. Among the most notable were

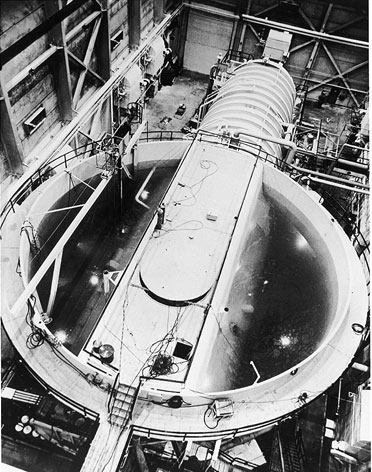

Various new submarine designs were developed during the interwar years. Among the most notable were submarine aircraft carrier

A submarine aircraft carrier is a submarine equipped with aircraft for observation or attack missions. These submarines saw their most extensive use during World War II, although their operational significance remained rather small. The most fam ...

s, equipped with a waterproof hangar and steam catapult to launch and recover one or more small seaplanes. The submarine and its plane could then act as a reconnaissance unit ahead of the fleet, an essential role at a time when radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

was not available. The first example was the British , followed by the French , and numerous aircraft-carrying submarines in the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

.

Early submarine designs put the diesel engine

The diesel engine, named after Rudolf Diesel, is an internal combustion engine in which ignition of the fuel is caused by the elevated temperature of the air in the cylinder due to mechanical compression; thus, the diesel engine is a so-call ...

and the electric motor

An electric motor is an Electric machine, electrical machine that converts electrical energy into mechanical energy. Most electric motors operate through the interaction between the motor's magnetic field and electric current in a Electromagneti ...

on the same shaft, which also drove a propeller

A propeller (colloquially often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon ...

with clutches between each of them. This allowed the engine to drive the electric motor as a generator to recharge the batteries and also propel the submarine as required. The clutch between the motor and the engine would be disengaged when the boat dived so that the motor could be used to turn the propeller. The motor could have more than one armature on the shaft – these would be electrically coupled in series for slow speed and parallel for high speed (known as "group down" and "group up" respectively).

In the 1930s, the principle was modified for some submarine designs, particularly those of the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage of ...

and the British U class. The engine was no longer attached to the motor/propeller drive shaft, but drove a separate generator, which would drive the motors on the surface and/or recharge the batteries. This diesel-electric propulsion allowed much more flexibility. For example, the submarine could travel slowly whilst the engines were running at full power to recharge the batteries as quickly as possible, reducing time on the surface, or use of its snorkel. Also, it was now possible to insulate the noisy diesel engines from the pressure hull, making the submarine quieter.

An early form of anaerobic propulsion had already been employed by the in 1864. The engine used a chemical mix containing a peroxide

In chemistry, peroxides are a group of compounds with the structure , where R = any element. The group in a peroxide is called the peroxide group or peroxo group. The nomenclature is somewhat variable.

The most common peroxide is hydrogen p ...

compound, which generated heat for steam propulsion while at the same time solved the problem of oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements as wel ...

renovation in an hermetic

Hermetic or related forms may refer to:

* of or related to the ancient Greek Olympian god Hermes

* of or related to Hermes Trismegistus, a legendary Hellenistic figure based on the Greek god Hermes and the Egyptian god Thoth

** , the ancient and m ...

container for breathing purposes. This system was not employed again until 1940 when the German Navy tested a system employing the same principles, the Walter

Walter may refer to:

People

* Walter (name), both a surname and a given name

* Little Walter, American blues harmonica player Marion Walter Jacobs (1930–1968)

* Gunther (wrestler), Austrian professional wrestler and trainer Walter Hahn (born 19 ...

turbine

A turbine ( or ) (from the Greek , ''tyrbē'', or Latin ''turbo'', meaning vortex) is a rotary mechanical device that extracts energy from a fluid flow and converts it into useful work. The work produced by a turbine can be used for generating e ...

, on the experimental submarine and later on the naval .

At the end of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, the British and Russians experimented with hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscous than water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usually as a dilute solution (3%� ...

/kerosene

Kerosene, paraffin, or lamp oil is a combustible hydrocarbon liquid which is derived from petroleum. It is widely used as a fuel in aviation as well as households. Its name derives from el, κηρός (''keros'') meaning "wax", and was regi ...

(paraffin) engines, which could be used both above and below the surface. The results were not encouraging enough for this technique to be adopted at the time, although the Russians deployed a class of submarines with this engine type code named Quebec